Rabbi Sue Levi Elwell's Visit to Poland

Shabbat Chayei Sarah, Temple Beth Israel, Altoona, PA (22 November 2024)

Shabbat Shalom.

I began this year, 5784, with a remarkable and memorable journey. Your rabbi, Audrey Korotkin, has asked me to share something of that story with you. I hope that sharing my insights will spark some questions for you about your Jewish story: your Jewish past, your Jewish present, your Jewish future.

Since I retired from serving the Union for Reform Judaism for nearly two decades, I have been blessed to serve several congregations here in the U.S. I was exploring the possibility of service in Europe, and connected with Rabbi Haim Beliak, who has been working to support and fund Progressive Judaism in Poland for over two decades. After I met with the leaders of Beit Warszawa on ZOOM, they invited me to come to Warsaw for Sukkot and Simchat Torah.

As many of you know, your rabbi, Burt Shuman, z’l, served Beit Warszawa for several years after he left Altoona. You may know that he mastered Polish when he lived there! I learned that Burt’s legacy is deeply appreciated by those who were blessed to know him and learn with him.

I travelled to Warsaw to honor the legacy of my partner Nurit’s parents, both of whom were born in Poland, and were fortunate to make their way to Palestine in the mid 1930s, before the Shoah.

Rabbi Jeffrey Salkin, an American colleague, served as High Holiday rabbi in Warsaw, and Nurit and I arrived in Warsaw the day that Rabbi Salkin returned to the U.S. Beit Warszawa is now located in the city center in a open and welcoming space across the street from the Symphony. The congregation is small, and the majority of those who attend services are dedicated individuals on the path to conversion. Weekly Shabbat services are led by one of two lay leaders who have trained as shlichei tzibur, service leaders. I was partnered with Alina, who travels 5 hours to share her musical gifts with the congregation. I was also blessed by the presence of Marzena, an accomplished and amazingly gracious translator. I celebrated Sukkot and Simchat Torah and two Shabbatot with the Beit Warszawa community. Over the course of my two weeks in Warsaw, we gathered for prayer, for study, and for many meals in the small synagogue space. I was delighted to sit in our sukkah, and to share the mitzvah of lulav with those present. The etrog and lulav was a gift to the congregation from Michael Schudrich, the Chief Rabbi of Poland.

Some of you have been to Warsaw. I’d like to share some words about an essential destination for any Jewish tourist to this large, complex city. POLIN is the new museum that tells the extraordinary story of the 1000 year History of Polish Jews.1 The museum opened 2 years ago, and its signature building houses state of the art interactive exhibits that tell stories of our history that extended my knowledge and expanded my understanding of the depth and breadth of our people’s contributions to and deep roots in what is now modern Poland. Too many of us are aware only of the devastation of Polish Jewry and the 3 million souls who were brutally rounded up, imprisoned, forced to march across frozen tundra, and murdered in the Shoah. POLIN reminds us that Jews were not only residents but builders of modern Poland. Polish Jewish life was rich and varied and vibrant for centuries. Between the 1st and 2nd World Wars, Jewish political, intellectual, and social life was thriving in Poland. Jewish political and religious movements, Zionists, Agudas Yisroel, and the Bund established and sponsored schools, youth groups, orphanages, health care, sanatoria, libraries, sports clusbs, newspapers, theater, music and more. There were hundreds of Jewish newspapers published in Yiddish and Polish. Poland became a world center of Yiddish cinema and theater, along with the U.S. On the eve of the Holocaust, Reform Judaism was flourishing in Warsaw. The largest synagogue in Warsaw, the Great Synagogue, was a Reform synagogue built in 1878 and, at the time of its opening, was the largest Jewish house of prayer in the world. It was blown up by the Germans on May 16,1943.

Some of you have been to Warsaw. I’d like to share some words about an essential destination for any Jewish tourist to this large, complex city. POLIN is the new museum that tells the extraordinary story of the 1000 year History of Polish Jews.1 The museum opened 2 years ago, and its signature building houses state of the art interactive exhibits that tell stories of our history that extended my knowledge and expanded my understanding of the depth and breadth of our people’s contributions to and deep roots in what is now modern Poland. Too many of us are aware only of the devastation of Polish Jewry and the 3 million souls who were brutally rounded up, imprisoned, forced to march across frozen tundra, and murdered in the Shoah. POLIN reminds us that Jews were not only residents but builders of modern Poland. Polish Jewish life was rich and varied and vibrant for centuries. Between the 1st and 2nd World Wars, Jewish political, intellectual, and social life was thriving in Poland. Jewish political and religious movements, Zionists, Agudas Yisroel, and the Bund established and sponsored schools, youth groups, orphanages, health care, sanatoria, libraries, sports clusbs, newspapers, theater, music and more. There were hundreds of Jewish newspapers published in Yiddish and Polish. Poland became a world center of Yiddish cinema and theater, along with the U.S. On the eve of the Holocaust, Reform Judaism was flourishing in Warsaw. The largest synagogue in Warsaw, the Great Synagogue, was a Reform synagogue built in 1878 and, at the time of its opening, was the largest Jewish house of prayer in the world. It was blown up by the Germans on May 16,1943.

As many of you know, 3 million Polish Jews were murdered in the Shoah. It is estimated that 330,000 Polish Jews survived, most in the Soviet Union. Some returned to Poland, searching for living relatives or friends. But too often, they were not only unwelcome, but victims of antiSemitic pogroms.2

The final “exhibit” in the museum is a film that presents interviews with a range of Jews living in Poland today. As Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, the chief curator of the museum writes about this film: “It is a unversal portrayal of the present-day reality precisely because it poses the questions that concern us all—the questions about who we are, about our families, our fears and dreams, about Poland….(the film-maker’s) questions are addressed to each and every one of us.”3

I went to Poland to honor the legacy of my wife’s parents, Joseph/Yusek and Batia/Basha Spiewak Shein. Yusek was born in Czestochowa on April 21, 1915. In 1935, as a featherweight boxing champion, he bid his parents goodbye and travelled with the Polish Maccabiah team to Palestine. “Only the flag returned to Poland.”

In 1936 in Tel Aviv, Yusek met Basha Spiewak, who became the love of his life. Born in Lublin September 3,1914, in 1939 Basha returned to her native Lublin to try to persuade her family to emigrate to Palestine. Yusek financed that trip, hopeful that she would return and become his wife. Despite a harrowing journey, and a narrow escape from her home town, she returned to Palestine alone. Yusek and Basha married in a simple ceremony in 1940 and settled in Tel Aviv, sharing a 2 room apartment with another young couple. Like many of his generation, Yusek attended the university at night after working as a laborer for a full day, completing a course of studies to become a teacher. He served in the Hagana and, later, in the IDF, achieving the rank of lieutenant in the Corps of Engineers.

When the state was declared in 1948, Yusek danced in the streets of Tel Aviv with his 5 year old son, Michael, on his shoulders. A month later, during a cease-fire, Nurit was born.4

Nurit and I have been partners since 1991, living together in the United States, and since our retirement, dividing our time between Philadelphia and Tel Aviv.

I was fortunate to be able to visit Lublin, with the hope of learning more about Basha’s beginnings. First we travelled to Majdanek, the concentration, transport and work camp established by the Germans as an integral part of their plan to wipe out both the entire Jewish population of Europe and all other Europeans they considered enemies.

It was a beautiful day: bright and clear and nearly 60 degrees. Grass covers the vast Majdanek “campus” between the wooden buildings, many of which are original. There are also reconstructed structures and guard stations strategically placed so that prisoners were under 24 hour surveillance. My companions and I spent 3 hours walking in silence along the pebbled paths of pain that stretch across the vast camp.

Nurit had believed that her grandfather, Moshe Yosef Spiewak, her aunt Ruja and husband Shia, and their young daughter Mira, were all murdered at Majdanek. I said kaddish at the site of one of the destroyed crematoria, and wept for all the lives that were violently destroyed in this place.

Tidy homes and other buildings are easily visible on the periphery of the camp. One footpath led to a gate through which neighbors can enter the “campus.” It is chilling to think that the people who lived there were truly unaware that they were living next door to a dehumanizing transport and extermination center.

We drove to Lublin in silence. Waze helped us find the address of Nurit’s mother’s family home. We thought that we found it and I snapped photos. I discovered a plaque in the nearby pavement that indicates the boundary of the ghetto, which I later learned was a ghetto without walls or a fence, but clearly delineated and enforced boundaries between what was determined as Jewish and “Polish” Lublin.

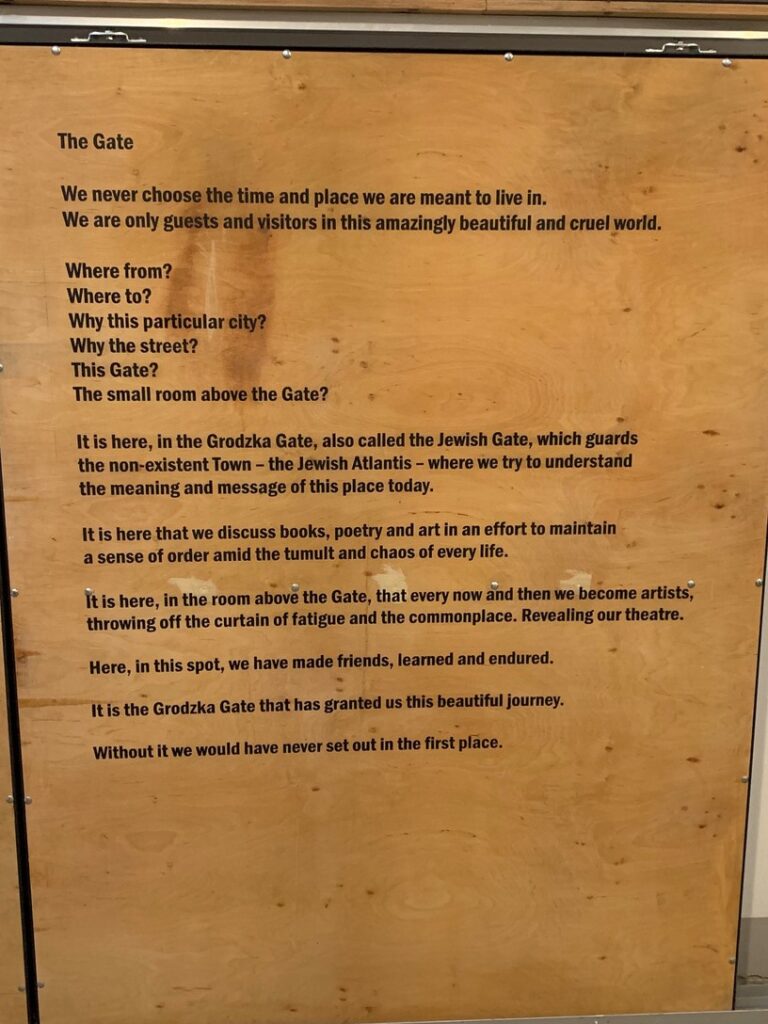

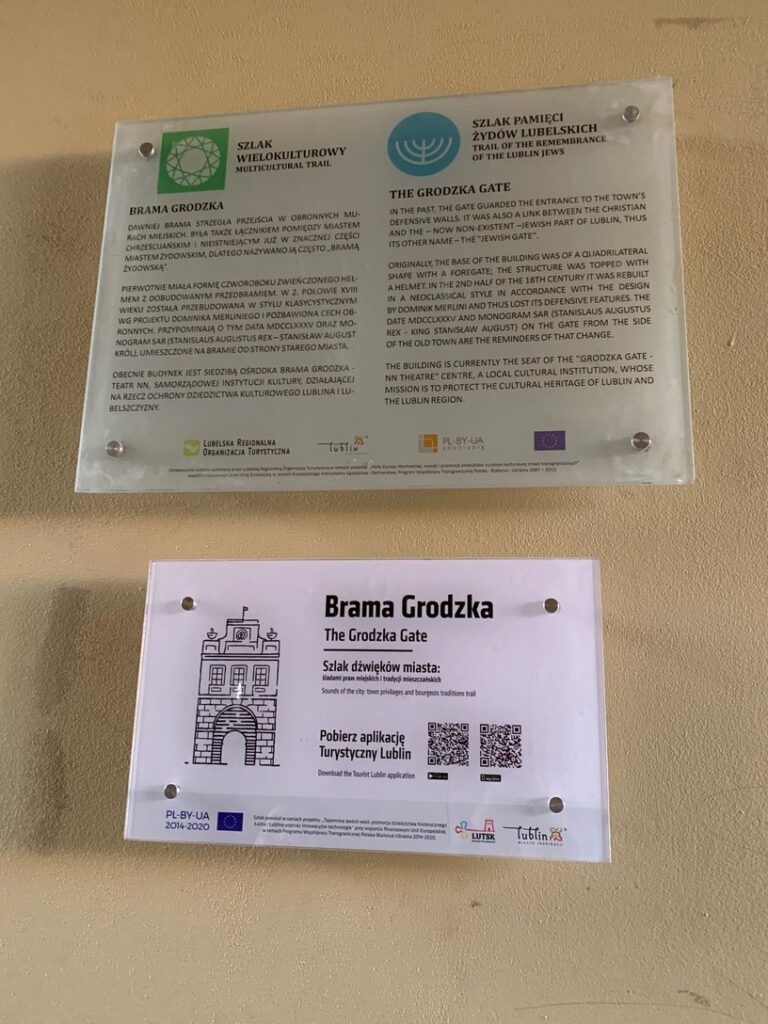

My companions and I then parked our car and walked over a cobblestone bridge that was the entrance to the former town center. We arrived at the Grodzka Gate Museum and met Tal Schwartz, a young Israeli who has been working as a photographer and tourism guide and planner in Poland for a number of years. She ushered us into the small shop associated with the museum. When I told her that we were looking for Nurit’s family’s home, she opened her computer. In the extensive data base of the Jewish history project of the Gate Museum, we almost immediately located Nurit’s grandfather’s addresses—the street numbers had changed—as well as photographs of his place of business. We excitedly called Nurit, who had returned to Tel Aviv.

My host had first met Tal in Czestochowa, the home of Tal’s grandfather. When I mentioned that Nurit’s father, Joseph Shein, was also from Czestochowa, Tal asked me whether he was a boxer. My eyes widened as I said yes! She then told me: “he was my grandfather’s boxing teacher! And boxing saved my grandfather’s life.”

We were both amazed—I then told her how special Nurit’s dad, Yusek/Joseph was. I met him in the early 1990s; he was in his late seventies. He was full of life, charming and curious about people, places, languages, and the world. His eyes sparkled as he spoke and he continued his love of sports, swimming several times a week and walking the streets of Tel Aviv. He was a person who attracted others. Into his 90s, as he would walk the streets of his beloved city, where he lived from 1935 until his death in 2010, his former students, some of them in their 70s and 80s, would stop him to say hello, and to share stories of their delight in having studied with him. ( I remember him telling us that one of his favorite things about retirement was to hear the morning school bells ring and know that he no longer needed to rush to the classroom!)

Tal and Nurit are now in touch, as Nurit is learning more about her family’s rich Polish-Jewish story.

I returned to Beit Warszava with a renewed appreciation for the dedication and devotion of the determined lay leaders who are struggling to revive our precious tradition in Poland, and with deep respect for each member of Beit Warszava who is studying Torah, learning Hebrew, and claiming the Jewish future as their own.

So this is my story. Each of us has a Jewish story, whether we were born into this challenging people or have chosen to walk this path. (Of course, each of us chooses to be a Jew every day.) And each of us has questions, the same questions posed in the film at the conclusion of our visit to the Polin museum: “ the questions about who we are, about our families, our fears and dreams, …questions are addressed to each and every one of us.”5

What is your Jewish story? What are your Jewish questions?

On this Shabbat, we read the Torah portion that is called Hayei Sarah, the life of Sarah. Yet this portion begins with Sarah’s death. Of course, each death invites a reckoning, an evaluation, a consideration of a life.

What is the story of your Jewish life?

May we each be blessed with a Shabbat of discrernment, of asking deep questions, a Shabbat of rest—and perhaps, a Shabbat on which we reflect upon and share our own sacred stories.

Shabbat shalom.

1The details included in this paragraph are based on POLIN: 100-Year History of Polish Jews, A Guide. Edited by Barbara Kirschenblatt-Gimblett (2022).

2Between 1945 and 1948, 150,000 Jews left Poland. Most countries closed their doors to the refugees. Bricha, an underground Zionist organization helped European Jews emigrate to Palestine. In 1968, a state sponsored anti-semitic campaign forced more than half of the 25,000 Jews then remaining in Poland to flee.

3POLIN, op cit., p. 127. Nurit and I were also privileged to have a guided tour of the Jewish HIstorical Institute, which is housed in a building across the street from, and damaged during the fire that consumed the Great Synagogue in 1943. We were mesmerized by the videos of the discovery of the Ringelblum Archive, a treasure trove of memoirs, diaries, newspapers, official notices, and documents of ordinary life in the Warsaw Ghetto that were hidden in metal boxes and milk cans and recovered after the war. One of the milk cans is on display. We weremoved by the intentional architecture and creative exhibit spaces that reflect and honor the courage, commitment and risk-taking of each of the Oneg Shabbat visionaries and participants, those who can be identified and those whose names are lost. I was particularly delighted to be gifted with a copy of Rabini Getta Warszawskiego, which includes biographical information on five rabbinic role models who cared for our people during the years of the Warsaw Ghetto with super-human compassion and wisdom.

5POLIN, op cit., p. 127.

RABBI MICHAEL A. SIGNER CLERGY CABINET PARTICIPATION FORM // CLICK HERE

VISIT THE CLERGY CABINET WEBSITE // CLICK HERE