On July 10, 2013 members of Poland’s Jewish community gathered in the town of Jedwabne in the Lomza region for a memorial service. At the memorial – one, lone, eye witness child survivor, Isaac Lewin was there to witness and interrupt the proceedings commemorating the events of July 10, 1941. The reflection below: “Jedwabne 2013” is about the events of that day. Other participants included a small group of Jews led by Cheif Rabbi Michael Schudrich and a few Poles. No participants from the town of Jedwabne. A few days latter the Polish press carried news of the forced retirement of The Rev. Wojciech Lemanski, a Catholic priest who organized the annual memorial visits to Jedwabne.

The anonymous “Jedwabne 2013” is focused on the elegaic encounter with memory and a few individuals finding (again) the burden of memory; the searing pain in the face of the other. The reburial of human ashes containing child’s shoes formed a hint of the past. (Bones reburied at site of 1941 Jedwabne massacre)

The significance and frequency of these ceremonies of memory is changing. We can trace a key moment in the changing nature of memory to historian Jan Gross’ May 2000 book entitled Neighbors. The book uncovered a dark past and set off a controversy in Poland that still reverberates. Gross’ research made clear that the anti-Jewish violence perpetrated by burning a barn with at least 300 Jews from the town in it, was not done by the occupying Nazi army but by neighbors. A Polish national commission, The Polish Institute of National Remembrance (Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, IPN) essentially affirmed the findings of Jan Gross.

A new pattern of memory – “countermemory” – “challeng[ed] the traditional image of Poles as martyrs and heroes in World War II ….” (Bringing the Dark Past, page 423). Poles were shocked. Some historians focused on a sober confrontation with the past. In 2001, the former mayor of the town Krzysztof Godlewski and the President of Poland Aleksander Kwaśniewski attended a ceremony at Jedwabne and offered apologies.

Other writers sought to re-write the history of the Jedwabne event. The “justification” claimed by some right-wing historians for the murder of their neighbors was that Jews had collaborated with occupying Soviets forces during the September 1939 to June 1941 period; under the Molotov (Soviets) – Ribbentrop (Germany) secret agreement the two enemies divided Poland. The versions and inventions continue around the difficult topic of national memory.

Poland has been the most courageous of the Eastern European countries in grappling with this difficult past that emerged since the demise of Soviet dominated Eastern Europe. It is a complex and difficult path with Polish historians, writers and politicians exhibiting a range of responses “from profound self-examination to passionate rejection.” (Bring the Dark Past p. 670). The tiny emerging Jewish communities have an important role to play in this effort.

The topic of the engagement with the “dark past” of Eastern European nations is the focus of a new book by John-Paul Himka of the University of Alberta and Joanna Beat Michlic of Brandeis University, Bringing the Dark Past To Light: The Reception of The Holocaust in Postcommunist Europe (University of Nebraska Press: 2013). The nearly 800 page study is framed by the editors who contribute their research on Ukraine and Poland, respectively as do chapters on seventeen other countries. A summary chapter by noted historian, Omer Bartov of Brown University attempts to decide and to referee a series of issues. Dr. Bartov cautions that: “the dark past we wish to bring to light is not as dead, and not as past as all that; it is still an active agent in formulating people’s understanding of the past and hopes for the future.” (Bringing the Dark Past, p. 663).

But now the intimate voice…”Jedwabne 2013.”

I saw a tiny feathered body lying by the doorstep just as I was leaving home. Another bird, the cat brings birds mice rats every day. I held it in my hand: its gray and brown feathers, the half-moon of a gently closed eyelid, you could almost see the lashes if birds had lashes, that is. The hard, firmly closed beak. Its wire-hanger feet. No breath. I wrapped the corpse up in a plastic bag and threw it in the bin.I drove to where my friends were gathered by the little van that was to take us to Jedwabne. A mild summer morning. On the bus I sat next to Zbyszek, saved from the Shoah by his mother’s Polish friend. We joked, we laughed. But as we approached the town the air shifted. It became dense, the mood eerie, uneasy. And then we couldn’t find the place where the barn had been. We asked a local man passing by, who said, Turn left right past the yellow house. Yes, one of the people on the bus said, good of him to have told us, sometimes they won’t even do that.

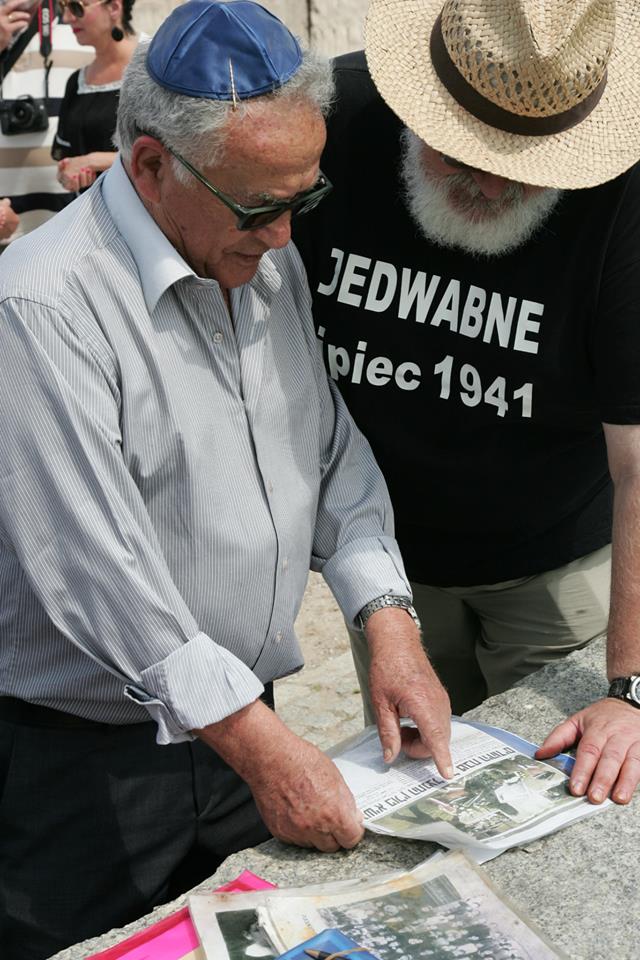

An expanse of field, yellowed parched grass, a dirt road leading to a rectangular space surrounded by a waist-high stone wall. Across the road, another wall, this one up to my chin. Behind it, matzevot stooping amidst unkempt grass. The sun ablaze. Must come here again to fix it, it’s all overgrown again, said my friend, a Jew who thinks himself not a Jew because he cannot believe in a just and loving God.I placed my hand on the low stone wall. Uneven, gritty. Whose cries, whose pleas are locked inside those stones? Are these even the same stones? I went up alone to the higher wall, meaning to pray. I couldn’t. I cannot pray by myself. I end up crying.So I returned to the lower wall. A brown-haired slight woman looked at me from behind dark glasses. Her face was contorted with sorrow. I whispered, “Shalom”. An elderly man approached her, and she spoke to him in Hebrew. In Hebrew, he asked me a question. I shook my head. He said, in gentle Polish, You have been crying. Yes, I answered. Why? Because I’m sad, why else, I said. At yehudia? he asked. Yes, yes, I whispered. He laughed, a joyous boisterous laugh, and held me to his chest. We were Jews together, so sweet. Never mind the sun, the memory, wherever are the ashes? He held me at arm’s length: You cried, he said. I nodded my head. He leant towards me: These people, they are all good people… but they’re not the people… But you, you are my sister. And, you know, he said, face burning, all my school friends had been burned in this barn, all of them, little children like me, boys and girls. I brought their photo. And they tell me they’ve just found a pair of child’s shoes here…

An expanse of field, yellowed parched grass, a dirt road leading to a rectangular space surrounded by a waist-high stone wall. Across the road, another wall, this one up to my chin. Behind it, matzevot stooping amidst unkempt grass. The sun ablaze. Must come here again to fix it, it’s all overgrown again, said my friend, a Jew who thinks himself not a Jew because he cannot believe in a just and loving God.I placed my hand on the low stone wall. Uneven, gritty. Whose cries, whose pleas are locked inside those stones? Are these even the same stones? I went up alone to the higher wall, meaning to pray. I couldn’t. I cannot pray by myself. I end up crying.So I returned to the lower wall. A brown-haired slight woman looked at me from behind dark glasses. Her face was contorted with sorrow. I whispered, “Shalom”. An elderly man approached her, and she spoke to him in Hebrew. In Hebrew, he asked me a question. I shook my head. He said, in gentle Polish, You have been crying. Yes, I answered. Why? Because I’m sad, why else, I said. At yehudia? he asked. Yes, yes, I whispered. He laughed, a joyous boisterous laugh, and held me to his chest. We were Jews together, so sweet. Never mind the sun, the memory, wherever are the ashes? He held me at arm’s length: You cried, he said. I nodded my head. He leant towards me: These people, they are all good people… but they’re not the people… But you, you are my sister. And, you know, he said, face burning, all my school friends had been burned in this barn, all of them, little children like me, boys and girls. I brought their photo. And they tell me they’ve just found a pair of child’s shoes here…

I turned away from him, I could not hear, I hid my face.

… with bones in them…

I wailed. I felt alarmed by my voice. And I felt shamed: by my face, by the noise I had made. A friend pressed my head to her neck. What? I whispered it back to her, his words, and as I did the wailing broke out again. My tender friend’s cheek was wet; whose tears? I felt fingertips touching me, comforting me, gentle fingertips stroking my arms, my hands, my back, numerous kind hands behind my back; whose hands? So many gentle hands.

I turned back to the man. His chest was showing in the opening of his shirt. There was a fly sitting there. I brushed it away. Underneath there was a drop of blood. My friend dabbed at it with a tissue. The crying man’s wife held my hand. He sank into my eyes and said, holding me: I am so glad I met you. I will give you my card. I want to stay in touch. You are my sister. My daughter. You are my true family.

But where is his family?

The ceremony started. The rabbi spoke, the priest spoke, names of the murdered were read, wreaths were laid, stones were placed upon the monument. It had happened right where we were standing, within the perimeter of those low walls, that the barn had stood into which the Poles of Jedwabne herded their town Jews and set them on fire. The man who had called me his sister kept interrupting the rabbi, the priest, to speak about the children who had died in that fire, to point to their little faces in the school photograph he’d brought. I am told he does it every year. Comes all the way from Israel every year and brings his photograph. The sun beat down and his schoolmates were burning alive right under our feet. The ground vibrated with anguish, with incomprehension, too holy to touch, how can we stand on it? And he, the man who had survived. Alone. Did he alone survive? How? Why? I am his sister forever, forever, but what is it that made him recognize?

Then they brought out a blue plastic container, and said they were going to bury the remains of a child who had been murdered there and whose body had just been found. A small container. Not a body after all – just the shoes and the bones of the feet of a child. My daughter is now six years old. People move up to see the burial. I cannot walk up. I am rooted to the ground. I cannot comprehend. I cannot accept. I hold on to my friend, who is weeping. A man to my left is making faces to stop himself crying. A young guy with a beard and tzitzit looks sadly in the direction of the rabbis. I love the sight of tzitzit. Today it does not comfort me. The rabbis intone the kaddish. I answer. I call out. It is consoling to hear living voices answer the call. But life explains nothing and makes nothing better.

On the bus, Zbyszek says to me: You were moved because you do not often go to these things. One gets accustomed.

I get a call from my friend, then another, and another, the next day. They want to know how I am doing. I love them then. Would they burn me alive in that barn? Would I burn them alive in that barn? And the cat brings in another dead bird. I pull gingerly on its neck until a gentle click. I wrap the corpse in a plastic bag and place it in the bin outdoors. It is hot outside.

Leave a Reply